Can You Maintain Self-Esteem While Pursuing Self-Improvement?

How can you be happy with where you are if it’s not where you want to be?

My career as a stand-up comedian was defined by a constant sense of lack. I wasn’t on the roster at certain comedy clubs. I couldn’t get booked on cool independent shows. I was rejected from comedy festivals. I didn’t have representation in the form of a manager or an agent. I couldn’t write that one killer joke that would work every time and set me apart from the rest of the field. I could go on and on, listing all of the things I was reaching for that always managed to elude my grasp. The point is, when I look back on my time as a comedian, it all feels like one big blur of longing and failure. The only other emotion that manages to sneak into those memories is the way I reacted to that failure - through a constant desire and effort to improve myself.

Mike Birbiglia has one of my all-time favorite quotes about the mindset of stand-up comedians. On his album Sleepwalk With Me he says, “There’s so much failure, and amidst that failure you have to tell yourself ‘It’s going quite nicely.’ Because if you didn’t, you’d never get onstage again.” The title of that track is called, simply, “Delusion.”

I don’t think my lies to myself ever went so far as “It’s going quite nicely,” but I definitely kept telling myself “This is going to work out.” I believed it too. I couldn’t conceive of a future where I wasn’t a full-time comedian. I worked too hard and wanted it too badly for it to not eventually become reality. But I knew I wasn’t there yet and had a massive gap to close. The question was, how was I going to close it?

As someone who is naturally averse to the machinations of networking (Both social and real-life) and finds the concepts of marketing and personal branding akin to something like The Dark Arts, I only saw one viable path forward: Get so good that you’re undeniable. It’s an old adage that every artist hears when starting out in their field, and it’s mostly bullshit. There are a select few out there who can rise up based on their abilities alone. The rest of us need a helping hand from others to get to the next level of our careers. But I didn’t know this at the time, so I drank the Kool-Aid and thought I could make myself into who I wanted to be through sheer force of will.

The goal I was after was authentic artistic awareness and expression. If I could open up and unlock the truest parts of myself, I could write jokes that would be undeniable, stand out, and get me to where I wanted to be. The list of things I tried to achieve this end is practically inexhaustible.

I worked through Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way. I went to therapy. I woke up early and journaled. I took a heroic dose of psychedelic mushrooms. I went to even more open mics and bad bar shows than usual. I wrote jokes and rewrote them and threw them out and wrote new ones and then rewrote those. I rediscovered an obsessive childhood reading habit, plowing my way through a mixture of self-help books and classic literature. I did a breathwork class. I watched biopics and studied the life stories of great artists, trying to find something I could emulate or apply to my life. I did exercises to correct my posture (I thought this would improve my stage presence, or something. I don’t know, I was really grasping at straws at this point). I meditated. I wrote some more jokes and did some more open mics and bad bar shows. I did another heroic dose of psychedelic mushrooms. None of it worked, and I got more and more upset.

Sometimes I think trying so hard had an inverse effect and actually held me back in the long run. I think of Princess Leia talking to Grand Moff Tarkin in Star Wars. “The more you tighten your grip, the more star systems will slip through your fingers.” In reality, there’s a paradox at the heart of trying to improve yourself, and I got caught up in it big time.

If you set off on a path to improve yourself, you’re admitting two things. One, you’re not who you want to be. Two, you could be that person if you made a concerted effort. The person you could be acts as a type of judge, an ideal you compare yourself and your progress to. Moving towards that ideal makes you feel better, but at the same time, you are always falling short of that ideal, no matter how much progress you’ve made. The solution to that is to compare yourself to who you were yesterday, not your ideal future self. But that feels like a cope sometimes. Even when you try to ignore it, the person you want to be is always off in the distance, shaking their head in disapproval.

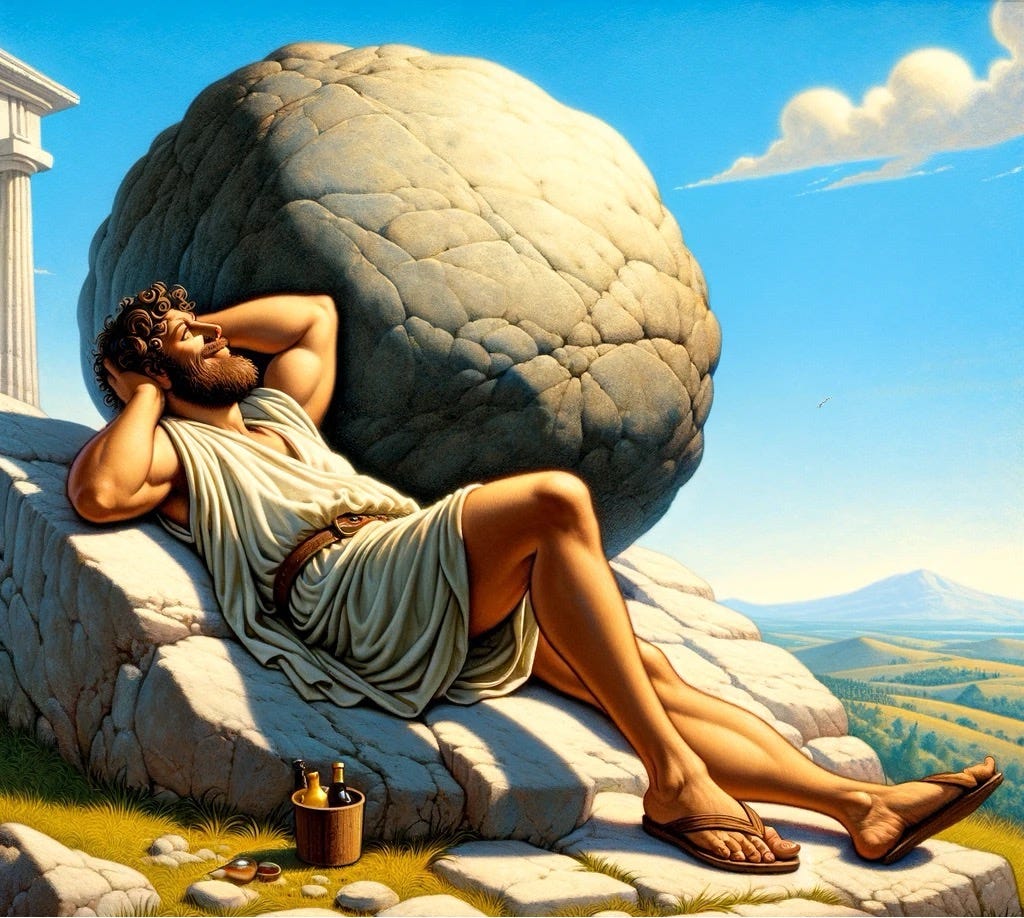

During these many years of attempted self-improvement and growth, I had several friends and peers who hadn’t seen me perform in awhile tell me, “You’ve gotten a lot better.” That was nice to hear, and it was a good example of comparing yourself to your previous self and not an imaginary future one. But I didn’t feel like I was getting better, both in terms of my comfort level on stage and the resultant net growth of my career. Whatever improvement I had achieved, it wasn’t enough. So I kept pressing onward, and kept feeling like I was falling short of my ideal, and that led to my eventual burnout and loss of interest in stand-up. I didn’t have it in me anymore to continue trying to move the immovable object.

So how do you solve this fundamental problem? How can you admit to yourself that you’re not where you want to be without that breaking down your self-esteem? Is it even possible? After all, saying you want to improve yourself is, at its core, an acknowledgement that you’re deficient in some way. You wouldn’t want to improve yourself if you were feeling just fine about who you were. But you’re most likely never going to reach the ideal you’re striving for. So how can you pursue improvement without the attending negativity that comes when you inevitably don’t measure up to your standards?

These were the questions that spun around in my head during this entire process. I eventually found the answer, but it came a bit too late. It took me getting out of stand-up to realize this, but I was missing a fundamental ingredient while I was pursuing this path of self-improvement, maybe the fundamental ingredient: Forgiveness.

If you want to make any legitimate progress, or at least not drive yourself crazy while you’re trying to get better, you can’t act as a taskmaster to yourself. Standing over your own shoulder and continually pointing out your shortcomings, like an inner J.K. Simmons in Whiplash, is a recipe for disaster. Whatever that voice is, that harsh judge, you can’t listen to it. It’s never content with making progress compared to who you were yesterday. It wants to reach the end game right now. And it’s that brutal judgment which will most likely prevent you from ever getting there in the first place.

You can have high standards. You can work to hold yourself to them and acknowledge when you fall short. But you must, must, cut yourself some slack when that moment comes. It feels like letting yourself off the hook, but it’s actually more difficult than simply raging against your own failures. It requires an elevated mindset, one that is more caring, open-minded, and dare I say spiritual. Because something resembling spirituality is what’s needed if you want to press forward and not be held hostage by your expectations at the same time. You have to maintain a belief, a literal act of faith, that your effort is going to pay off and it won’t all be for naught. And you simply have no choice but to forgive yourself in the moments that it doesn’t. To quote J.K. Simmons’ character in Whiplash (Who is talking about something completely different when he says this but I still think it applies), “I believe that is an absolute necessity.”

Side note that I just want to drop in here, lest anyone think I’m speaking poorly of this movie, but I believe Whiplash is the greatest film of the 21st century. This certainly won’t be the last time I mention it on this Substack. Some people get hung up on the intensity of it and say that’s not how art works. To me, much like the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, it’s meant to be taken metaphorically and not literally. You don’t need to be an insane, brutalist, psychopath asshole to succeed in life. What you do need is a high level of intrinsic drive, high standards, and a high tolerance for failure. I think the tolerance for failure part is where I fell short. I just took everything too personally. Okay, side note over.

I didn’t learn the importance of forgiveness in time to apply it to stand-up, but I try and put it into practice now. Even though I’m not pursuing comedy anymore, I still have goals. I want to make this Substack as good as I possibly can. I would like to get in really awesome shape, like Ben Affleck in The Town levels of good shape. I want to display competencies at work so I can get promoted and earn more money for my future family. There are days where I fall short of these goals. Sometimes I write all morning and realize everything I’ve put down absolutely sucks. Some weeks I eat like complete garbage and don’t make any progress with my fitness, or worse, backslide. Occasionally, my PowerPoint presentations look like shit and need to be redone. But instead of beating myself up over this, I forgive, apply my learnings, vow to seize the next opportunity to be better, and move on. Most importantly, I trust that I will get better over time. Not only does this help me improve, it lets me feel pretty okay about myself while I’m doing it. It’s hopeful and aspirational, while leaving the right amount of space for criticism and growth. That’s all I ever wanted from my stand-up experience. I wish I could have found it there, but it’s better to have found it late, and in a different place, than to not have found it at all.

Hell yeah