I Am So Tired Of Nathan Fielder’s Whole Thing

I’m deeply opposed to his project, on both a comedic and human level

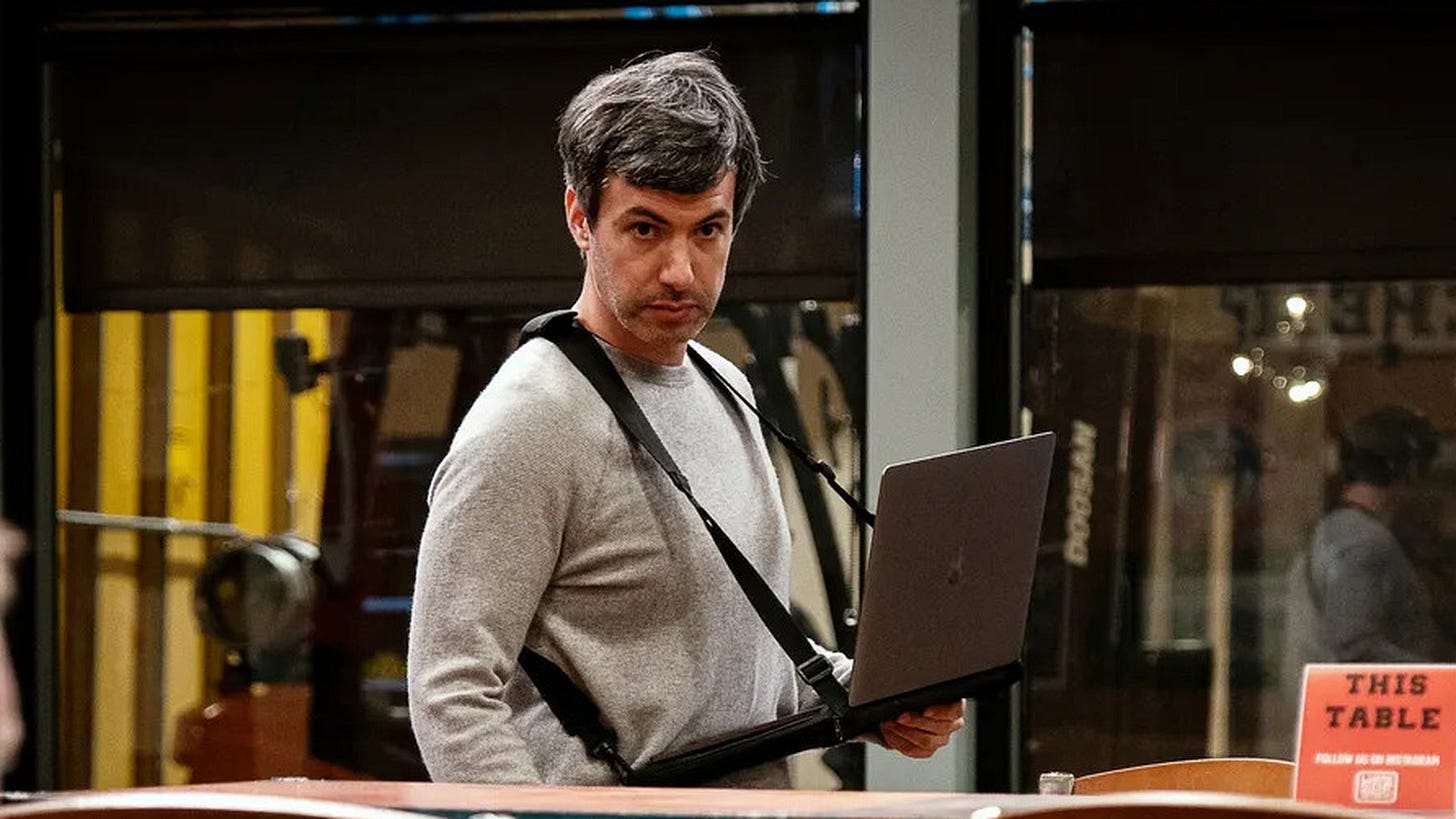

Nathan Fielder is a real-life Batman villain.

He’s also the creator and star of two acclaimed comedic reality shows: Nathan For You (Comedy Central, 2013–2017) and The Rehearsal (HBO, currently airing on Sunday nights), but I mostly want to focus on the Batman thing.

Fielder is clearly brilliant. That much is obvious when you watch him on either of his shows. He concocts elaborate scenarios that pay off in completely unexpected ways. Whether he’s helping a small business compete against a corporate rival, or coaching someone through an important personal challenge they’ll soon have to face down, you’re witnessing a one-of-a-kind mind at work. To top it all off, his schemes always include a streak of surrealist humor, adding another variable to an already difficult challenge. He’s extremely talented and has more than earned his success and devoted fanbase.

I just absolutely hate everything he’s doing, and I always have.

The reason Fielder reminds me of The Riddler (If, instead of robbing banks, The Riddler landed an overall deal with Viacom) is the deviousness that underlies all of his meticulously crafted plans. There’s something incredibly mean-spirited about his process, a falseness that betrays a cold and dark worldview. It permeates everything, from the themes he engages with to the jokes that he makes, and I find it completely at odds with the way I personally experience and move through the world.

In Nathan For You, Fielder presents himself as a business school grad helping small businesses get a leg up on their corporate competition. He devises outlandish marketing schemes (Like selling plasma TVs for $1 so Best Buy has to price-match) and shares them with the business owners in his trademark deadpan cadence. The joke is that Fielder says something completely ridiculous in a very serious tone, and then the business owner is forced to react to the incongruence between Fielder’s words and his affect. A lot of times they’re so taken aback they just go along with it.

However, the comedy here is darker and more insidious than it first appears. On the surface, Fielder is the fool in these situations. He’s the one coming up with and enthusiastically executing these ridiculous plots. But Fielder is playing a character. I’ve watched enough interviews with the real Fielder to know that the man we see on the show is not the same guy. They’re similar, but TV Fielder is a heightened version of off-screen Nathan. It’s like professional wrestling, where Steven Anderson takes his genuine redneck attitude and love of beer, turns the intensity all the way up, and walks to the ring as Stone Cold Steve Austin.

Because of this distinction, it’s really the small business owners and their customers who are the butt of the joke. Nathan Fielder, the real man behind the character, is simply toying with them, like a cat with a ball of string. He’s using his superior intelligence and high tolerance for discomfort to manipulate them into going along with his plans, and putting it all on TV to boot. We, the viewing audience, are meant to find enjoyment in watching his subjects squirm. He intentionally agitates in order to get laughs.

Fielder takes this gambit one step further in The Rehearsal. Now, I’ll readily admit, I’ve only seen two episodes of The Rehearsal (The premiere, and Season 2’s “Pilot’s Code,” which I’ll get to shortly). I had planned to watch all ten currently available episodes as research for this essay, but I just couldn’t take any more of this show.

The premise of The Rehearsal is that Fielder helps everyday people prepare for stressful situations by allowing them to rehearse well in advance. In the premiere, he builds a perfect replica of a real Brooklyn bar and hires dozens of actors so someone can rehearse sharing a secret with a close friend for the first time. It’s a deeply off-putting viewing experience, and not just because everyone involved, from the confessor to the confidant to Fielder himself, aren’t the most graceful when it comes to social situations.

If The Rehearsal is to be taken at face value, it fully lays bare Fielder’s worldview. Other human beings are not perceived as embodied souls, they are simply points of data on a chart that can be measured and manipulated to suit personal ends. No one really exists, and everything is stripped of mystery or emotion. Reality is nothing more than the sum of its parts. All you need to make it through life is enough data and a reliable decision tree that you can reference. The world might as well be a computer program. It’s the bleakest kind of nihilism.

Watching someone as intelligent as Fielder operate in this way is both depressing and infuriating. Surely, he has to be aware that this is no way to go through life. He certainly hints at it throughout the show. I just don’t understand what he’s getting out of this. And if he doesn’t endorse this worldview, why spend so much time, energy and money on something that perpetuates it? Maybe there’s a deeper message that I’m not picking up on, but as it stands, I just can’t get on board with anything he’s attempting to do here.

Fielder also relies heavily on irony, another pet peeve of mine. The aforementioned “Pilot’s Code” episode hinges entirely on one joke, the butt of which is the 2003 nu metal song “Bring Me To Life” by Evanescence.

The details of this episode is too intricate to fully get into here, but essentially Fielder argues (And reenacts through increasingly bizarre set pieces) that heroic airline pilot Captain “Sully” Sullenberger was able to safely land a distressed US Airways flight in the Hudson River back in 2009 because he was listening to “Bring Me To Life” on his iPod while guiding the plane into the water. He deduces this by going through Sully’s memoir, claiming that the topic of his iPod keeps coming up and that, when discussing his favorite music, “The one band [Sully] mentions more than any other is Evanescence.”

This claim appears to be false. According to an article on Cracked.com (Not the most well-regarded source for journalism, but still) “Sully only ever mentions Evanescence once, as part of a long list of musicians he likes, which also includes Natalie Merchant, The Killers and Green Day.” So why did Fielder claim otherwise? Cracked has a theory.

“It would appear that Fielder selected Evanescence for this bit, not because Sully was necessarily a huge fan, but because, with apologies to the band, they were the hands-down funniest choice.”

What’s so funny about them? Why pick on Evanescence here? I know exactly why. It comes from what Dudley Newright calls “Millennial Snot.” Millennial Snot is the type of humor that thinks making fun of Guy Fieri and Nickelback is the height of comedy. It’s smug, snarky and condescending, found in any kind of irony poisoned joke used by hipsters to signify how cool and over it they are. From this perspective, the mere existence of a song like “Bring Me To Life”, so inferior to the refined rock music of the indie sleaze era, is a punchline. When you can pair it with an intense real life scenario like The Miracle On The Hudson, the dichotomy makes it that much funnier.

Well, fuck those people. I like that song, and I genuinely enjoy the genre of music it belongs to. I was in the gym a few weeks ago when Rob Zombie’s “Dragula” came on, and it was awesome. I mean that with all sincerity, no hint of irony to be found.

Fielder’s worldview and sense of humor are in complete alignment. Irony and nihilism go hand in hand. If nothing means anything, then nothing is really worth joking about. The only thing you can joke about is pretending to care, hyperbolically praising and endorsing mundane, everyday, or even base things. But there’s no joy or true humor in that, it’s just one overwrought cry for help. Irony, in the words of David Foster Wallace, “is the song of a bird that has come to love its cage.”

I know there are Fielder fans out there who will claim there is genuine emotion in his work. They’ll point to the Nathan For You finale “Finding Frances” where Fielder helps a Bill Gates impersonator reconnect with his long lost love. I watched that in preparation for this essay, and it did nothing for me. The final phone conversation between the former lovers was riveting, but everything around it fell flat. The journey to actually find Frances was more of the same nonsense that turned me off of Nathan For You in the first place. And don’t get me started on the B plot where Fielder gets involved with a personal escort. That was unbearable the whole way through.

Contrast Fielder’s attempts at sincerity with that of another HBO series, How To With John Wilson. Fielder serves as an executive producer on this show, but its message couldn’t be further from that of his personal projects. How To has the same sort of detached, awkward tone, but you can feel a genuine sense of wonder and appreciation for humanity coming through at all times. This is helped by the fact that Wilson himself is rarely seen on screen. He exists as a sort of roving eye, moving all over New York City, overlaying what he films with dry but sympathetic commentary. Fielder, on the other hand, is a constant presence in his shows. He’s always there, visibly judging, mocking with his deadpan stare.

One of the standout episodes of How To revolves around a group of fans of James Cameron’s Avatar. Not only do they love the movies, but they fluently speak the language of those giant blue creatures, the Na’vi. Wilson spends an inordinate amount of time with them and dives into not just the workings of the group, but the personal struggles and frustrations that ultimately led to them taking up such a niche hobby. In spite of the obvious absurdity, he never turns these people into caricatures or loses sight of their humanity. From this vulnerability, provided by both Wilson and his subjects, comes true, genuine, good-natured humor. We laugh, and we feel more connected to people who are nothing like us.

Fielder could never do this. He would try to play the Avatar fans for laughs, avoiding any opportunity for real intimacy. He could also never direct a Bon Iver music video for a song called “Everything Is Peaceful Love.” That’s just way too sincere.

There are a couple more weeks of Season 2 of The Rehearsal left on HBO. I’m sure it will culminate in another groundbreaking episode, something that nobody else would have been able to dream up, much less pull off. The praise it receives will be justified and well-deserved. I just simply won’t care. This show, and Fielder’s work so far, has nothing to offer me, and I have no desire to engage with it.

Or maybe I’m just a huge square that can’t appreciate a good prank. It’s entirely possible. I never liked Punk’d when it was on TV either.

This article seems to miss the entire point of Nathan's whole shtick—human relationships are undeniably uncomfortable, but rather than suffer over them, we might as well have a laugh at them. I think anyone who's ever struggled with social interaction tends to love this show because it's a reminder that it's not all that deep.

Thank you. You have perfectly encapsulated a feeling I could never quite put my finger on.

The whole spectrum of prank comedy, from its very lowest to its higher expressions (Candid Camera -> Nathan Fielder), has the same premise.

We stand and laugh at normal people, for the same reason: "Ha ha! You accepted a reality as it was presented to you! You interacted with other human beings in good faith! Ha ha! What an idiot!"

It's not pleasant.